|

Passive Solar Neighborhood—One Story

Carolina Sun, by Bob Powell Incoming NCSEA Chair | Winter 1991

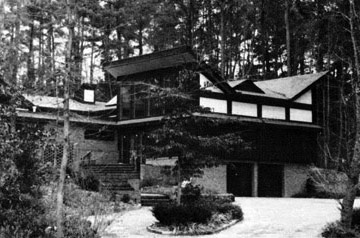

| | The "butterfly house," one of the most striking solar homes in Durham's Green Mill passive solar development. |

Freeman Ledbetter is one of the more unusual solar builders in the state. He was a practicing biochemist at Duke University when he decided to build solar homes. His first development, Green Mill, is in the Hope Valley section of Durham and consists of 33 lots. The neighborhood includes several unique contemporary solar designs. I recently talked with Freeman about Green Mill and what he's up to today. It's a nice place to visit. Feel free to call Freeman—I'm sure he'd love to show you around.

Bob: When did Green Mill start and how did you get started with that?

Freeman: Green Mill as a concept probably started back in 1973. The property was initially owned by a black family named Green. And we started working with them in 1975. Initially they owned about 200 acres in this area. By the time I met them they had only about 60 left. The two surviving brothers, Kyrus and Marcellus, were sitting on this property and paying taxes on it. They couldn't sell it, they couldn't even give it away. They, as a last resort, had decided to sell all the lumber off this property to help pay the taxes. That's what they were getting ready to do. I tried to work out a deal with them to buy the property and assume the tax liability and work out a develop¬ment plan.

Because of the relationship we had with them, we dedicated this whole thing to them. They had been on this property since 1892, when their father was in the sawmill business. They still had the sawmill that had been closed down. When we did the development, we named it Green Mill in memorial to them. The fixture at the entry is the old boiler that used to fire the steam engine from the mill.

B: I always thought that solar construction was what got you started in this business, but that really came later.

F: It came when we started to try and figure out what we were going to do with this property. My brother Clarence and I planned this whole thing. We tried to brainstorm and come up with something. We asked ourselves "What can we do with this property that is going to be unique enough to make it very desir¬able?"

At that time the price of heating fuel was going skyhigh. We started looking around trying to find people who knew something about solar energy, and we ran into Bruce Johnson. Bruce did the original consulting work on architectural design and passive solar. We didn't actually build any of his houses. We built one that is a modification of his design—the Miller house. That was one of his that we made some modifications to. But Bruce sort of put us on the track of what solar energy was. He guided us in the right direction.

We also got with Ken Coulter, who is a local landscape architect. Ken did the actual layout for Green Mill. The lots are laid out so that everybody's got a southern exposure. Everybody's got enough land between houses, at least 70 feet, so that everyone has access to the sun. We even wrote into the covenant a guaranteed solar sccess.

B: Isn't Green Mill one of the earliest neighborhoods in North Carolina to have guaranteed access?

F: It was the only neighborhood east of the Mississippi at that time that was done as a solar community.

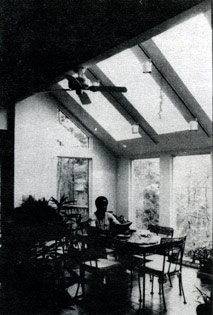

| | Freeman Ledbetter in his own solar home in Green Mill. |

B: And so the covenant provides solar access for every lot?

F: Yes. Your neighbor to the south—if he's got any evergreen trees that are blocking your lot, he's got to take them down.

B: Given the design of the lot, once the houses are in, there's probably not a strong chance that another house would have its access blocked. But what you're saying is that evergreen trees eventually could be an access barrier.

F: Right. Actually, we've never had to go next door and tell someone to cut trees down. That's because there's enough space between houses so it hasn't been a real problem.

B: So the layout of the lot is more critical in assuring solar access.

F: You try and orient the long axis of the lot north-south, if you can. Then the southern exposure of the house will be facing the street, which is good. Those people will probably have the best access to the sunlight. Or you're facing away from the street toward the woods. Li any case, you will still have pretty good access because the trees are not too large. But the added advantage is that you have a beautiful view looking out in the woods.

B: The streets in Green Mill are not all at right angles. They do curve around. Was this a problem?

F: No. Most of the houses are oriented on the lots to face the street or a little bit to the right. But nobody is ever looking at the side of anybody's house.

The other thing is that because every-body is open to southern exposure, and therefore all in the same direction, my neighbor won't have a lot of glass on their north side to look back at me.

B: One of the things that's interesting about Green Mill is the variety of archi-tectural styles and solar technologies in the neighborhood. How about describing some of them.

F: The first house as you enter the neigh-borhood is owned by a prominent attorney and his wife. When they asked me to build them a house, they took me down to Hope Valley and showed me a traditional, two-story Georgian brick house. He told me that was what he wanted. His wife said she wanted something with a contemporary open plan. So we took a plan and facade of a two-story Georgian house and took out some walls, and took out some floors, and opened the thing up, but we still had that facade.

His house has active solar hot water heating, extensive south facing glass, masonry floors on the first floor, and a woodstove with masonry walls. The house is about 3200 square feet, as opposed to their former house which was about 1800 square feet. The cost of living in this larger house is about one-third the cost of living in the smaller house that they used to live in. This was the opportunity to come up with a very traditional-looking house mat has all the passive solar features and active solar.

B: That house has an interesting window insulation system.

F: It has motorized window insulation curtains that are thermostatically controlled. When it gets cold outside at night, they automatically come down.

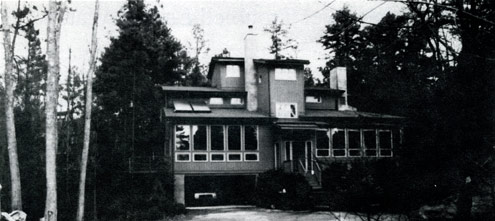

| | One of the conventional passive solar homes that Ledbetter built in Green Mill. |

B: It's been working well?

F: That house is about eight or nine years old with no problems. One of the down sides of the solar industry is that there were all these companies that sold solar products who are no longer here. They're gone. And they had good products. The loss of tax credits has been a real problem. The window shades were subject to the tax credits.

B: A lot of the houses have active solar. Did they come from different companies?

F: We used mostly systems from Astron Technologies. Every house was a different experiment.

B: One of the houses has a breadbox type collector, doesn't it?

F: That is actually on a house that Bob Calhoun built. We changed a little something here and little something there. We built a house for the Millers over there—it was a take-off on Bruce Johnson's design. That house is probably the one that has the most thermal mass inside. Its electric bills for July and August have been as low as $23 during some very hot summer months. The house has two-story brick walls, eight inches thick around the stove. With all that mass, that house is very efficient.

The Coffcy house has a masonry floor, interior masonry walls, and the insulated curtain wall. The house over there was built by the owner. It was basically a traditional house but he used six-inch insulated walls. He's got brick floors inside and a domestic solar hot water system. And he's got a wood boiler that heats water for space heating.

B: What kinds of systems are you working with now?

F: The houses we arc building now try to incorporate the experience from all our past houses. The smaller houses we build now are very efficient. The other tiling we are using now is stressed skin panels. These houses will be tighter than any we have ever built. As such, we will have to address the ventilation problem. We are able to buy equipment that will do everything: heat water, heat the space, air condition the space, ventilate the space, everything all in one unit. In these homes we will be using gas fired units as much as we can. There arc also radiant floor systems using gypcrete with pipe, the control module and thermostat.

One other thing we're going to try in a 2600- square-foot house in North Durham, which will have a 1600- square-foot radiant floor, will be to bury about 500 feet of line in the ground and circulate water through it to cool the house in summertime. It's probably going to be okay, but would work better if we could place some fins on the ceiling.

B: How will the space be cooled? With air?

F: No, with water. Cold water through the floor.

B: Radiant cooling through the floor? You could freeze your tootsies off!

F: It may work okay. It would work better if we had it in the ceilings because that's where the hot air is. But we're just going to do it and see how it works. I'm sure it's going to do okay because that's how the Miller house works. You've got all that masonry in there that acts as a heat sink.

B: I wonder if the active cooling is necessary. Like you said, a large thermal mass acting as a heat sink is quite effective.

F: These houses may have some overkill because those floors arc sitting on the ground, too.

B: That's one of the things about a lot of your houses. You experiment with nonconventional systems and you integrate two or three of them together.

F: It is an attempt to produce affordable, high quality housing mat is both energy-efficient and environmentally sound. I guess a passage given to me by Mrs. Miller, the owner of one of my houses, best describes what we are trying to do: "Sunspace, Ltd., designers and builders of custom homes that follow the natural flow of air and sunlight, which create new forms of architectural beauty while conserving energy."

|